What is JavaScript?

What is JavaScript?

JavaScript (js) is a light-weight object-oriented programming language which is used by several websites for scripting the webpages. It is an interpreted, full-fledged programming language that enables dynamic interactivity on websites when applied to an HTML document. It was introduced in the year 1995 for adding programs to the webpages in the Netscape Navigator browser. Since then, it has been adopted by all other graphical web browsers. With JavaScript, users can build modern web applications to interact directly without reloading the page every time. The traditional website uses js to provide several forms of interactivity and simplicity.

Although, JavaScript has no connectivity with Java programming language. The name was suggested and provided in the times when Java was gaining popularity in the market. In addition to web browsers, databases such as CouchDB and MongoDB uses JavaScript as their scripting and query language.

| Prerequisites: | Basic computer literacy, a basic understanding of HTML and CSS. |

|---|---|

| Objective: | To gain familiarity with what JavaScript is, what it can do, and how it fits into a web site. |

A high-level definition

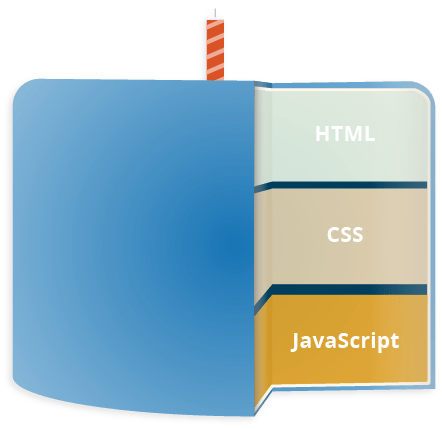

JavaScript is a scripting or programming language that allows you to implement complex features on web pages — every time a web page does more than just sit there and display static information for you to look at — displaying timely content updates, interactive maps, animated 2D/3D graphics, scrolling video jukeboxes, etc. — you can bet that JavaScript is probably involved. It is the third layer of the layer cake of standard web technologies, two of which (HTML and CSS) we have covered in much more detail in other parts of the Learning Area.

- HTML is the markup language that we use to structure and give meaning to our web content, for example defining paragraphs, headings, and data tables, or embedding images and videos in the page.

- CSS is a language of style rules that we use to apply styling to our HTML content, for example setting background colors and fonts, and laying out our content in multiple columns.

- JavaScript is a scripting language that enables you to create dynamically updating content, control multimedia, animate images, and pretty much everything else. (Okay, not everything, but it is amazing what you can achieve with a few lines of JavaScript code.)

The three layers build on top of one another nicely. Let's take a simple text label as an example. We can mark it up using HTML to give it structure and purpose:

So what can it really do?

The core client-side JavaScript language consists of some common programming features that allow you to do things like:

- Store useful values inside variables. In the above example for instance, we ask for a new name to be entered then store that name in a variable called

name. - Operations on pieces of text (known as "strings" in programming). In the above example we take the string "Player 1: " and join it to the

namevariable to create the complete text label, e.g. "Player 1: Chris". - Running code in response to certain events occurring on a web page. We used a

clickevent in our example above to detect when the label is clicked and then run the code that updates the text label. - And much more!

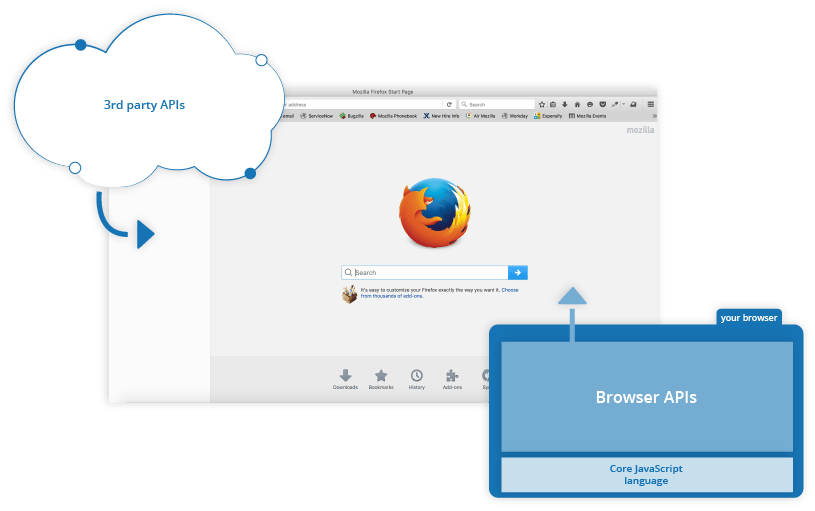

What is even more exciting however is the functionality built on top of the client-side JavaScript language. So-called Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) provide you with extra superpowers to use in your JavaScript code.

APIs are ready-made sets of code building blocks that allow a developer to implement programs that would otherwise be hard or impossible to implement. They do the same thing for programming that ready-made furniture kits do for home building — it is much easier to take ready-cut panels and screw them together to make a bookshelf than it is to work out the design yourself, go and find the correct wood, cut all the panels to the right size and shape, find the correct-sized screws, and then put them together to make a bookshelf.

They generally fall into two categories.

Browser APIs are built into your web browser, and are able to expose data from the surrounding computer environment, or do useful complex things. For example:

- The

DOM (Document Object Model) APIallows you to manipulate HTML and CSS, creating, removing and changing HTML, dynamically applying new styles to your page, etc. Every time you see a popup window appear on a page, or some new content displayed (as we saw above in our simple demo) for example, that's the DOM in action. - The

Geolocation APIretrieves geographical information. This is how Google Maps is able to find your location and plot it on a map. - The

CanvasandWebGLAPIs allow you to create animated 2D and 3D graphics. People are doing some amazing things using these web technologies — see Chrome Experiments and webglsamples. - Audio and Video APIs like

HTMLMediaElementandWebRTCallow you to do really interesting things with multimedia, such as play audio and video right in a web page, or grab video from your web camera and display it on someone else's computer (try our simple Snapshot demo to get the idea).

Third party APIs are not built into the browser by default, and you generally have to grab their code and information from somewhere on the Web. For example:

- The Twitter API allows you to do things like displaying your latest tweets on your website.

- The Google Maps API and OpenStreetMap API allows you to embed custom maps into your website, and other such functionality.

What is JavaScript doing on your page?

Here we'll actually start looking at some code, and while doing so, explore what actually happens when you run some JavaScript in your page.

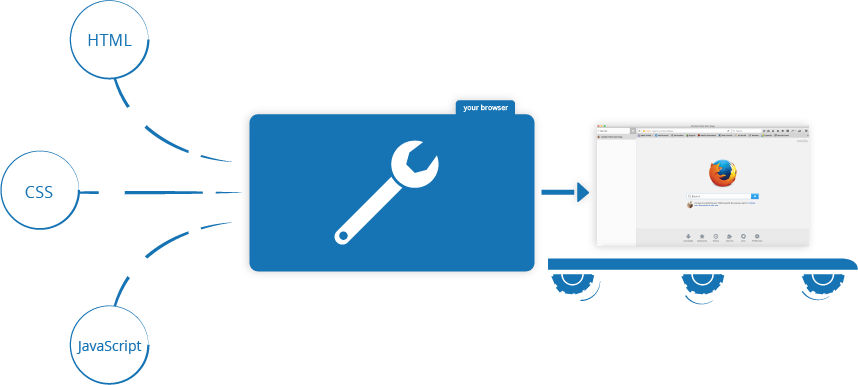

Let's briefly recap the story of what happens when you load a web page in a browser (first talked about in our How CSS works article). When you load a web page in your browser, you are running your code (the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript) inside an execution environment (the browser tab). This is like a factory that takes in raw materials (the code) and outputs a product (the web page).

A very common use of JavaScript is to dynamically modify HTML and CSS to update a user interface, via the Document Object Model API (as mentioned above). Note that the code in your web documents is generally loaded and executed in the order it appears on the page. Errors may occur if JavaScript is loaded and run before the HTML and CSS that it is intended to modify. You will learn ways around this later in the article, in the Script loading strategies section.

Browser security

Each browser tab has its own separate bucket for running code in (these buckets are called "execution environments" in technical terms) — this means that in most cases the code in each tab is run completely separately, and the code in one tab cannot directly affect the code in another tab — or on another website. This is a good security measure — if this were not the case, then pirates could start writing code to steal information from other websites, and other such bad things.

JavaScript running order

When the browser encounters a block of JavaScript, it generally runs it in order, from top to bottom. This means that you need to be careful what order you put things in. For example, let's return to the block of JavaScript we saw in our first example:

const para = document.querySelector("p");

para.addEventListener("click", updateName);

function updateName() {

const name = prompt("Enter a new name");

para.textContent = `Player 1: ${name}`;

}

Here we are selecting a text paragraph (line 1), then attaching an event listener to it (line 3) so that when the paragraph is clicked, the updateName() code block (lines 5–8) is run. The updateName() code block (these types of reusable code blocks are called "functions") asks the user for a new name, and then inserts that name into the paragraph to update the display.

If you swapped the order of the first two lines of code, it would no longer work — instead, you'd get an error returned in the browser developer console — TypeError: para is undefined. This means that the para object does not exist yet, so we can't add an event listener to it.

Interpreted versus compiled code

You might hear the terms interpreted and compiled in the context of programming. In interpreted languages, the code is run from top to bottom and the result of running the code is immediately returned. You don't have to transform the code into a different form before the browser runs it. The code is received in its programmer-friendly text form and processed directly from that.

Compiled languages on the other hand are transformed (compiled) into another form before they are run by the computer. For example, C/C++ are compiled into machine code that is then run by the computer. The program is executed from a binary format, which was generated from the original program source code.

JavaScript is a lightweight interpreted programming language. The web browser receives the JavaScript code in its original text form and runs the script from that. From a technical standpoint, most modern JavaScript interpreters actually use a technique called just-in-time compiling to improve performance; the JavaScript source code gets compiled into a faster, binary format while the script is being used, so that it can be run as quickly as possible. However, JavaScript is still considered an interpreted language, since the compilation is handled at run time, rather than ahead of time.

There are advantages to both types of language, but we won't discuss them right now.

Server-side versus client-side code

You might also hear the terms server-side and client-side code, especially in the context of web development. Client-side code is code that is run on the user's computer — when a web page is viewed, the page's client-side code is downloaded, then run and displayed by the browser. In this module we are explicitly talking about client-side JavaScript.

Server-side code on the other hand is run on the server, then its results are downloaded and displayed in the browser. Examples of popular server-side web languages include PHP, Python, Ruby, ASP.NET, and even JavaScript! JavaScript can also be used as a server-side language, for example in the popular Node.js environment — you can find out more about server-side JavaScript in our Dynamic Websites – Server-side programming topic.

Dynamic versus static code

The word dynamic is used to describe both client-side JavaScript, and server-side languages — it refers to the ability to update the display of a web page/app to show different things in different circumstances, generating new content as required. Server-side code dynamically generates new content on the server, e.g. pulling data from a database, whereas client-side JavaScript dynamically generates new content inside the browser on the client, e.g. creating a new HTML table, filling it with data requested from the server, then displaying the table in a web page shown to the user. The meaning is slightly different in the two contexts, but related, and both approaches (server-side and client-side) usually work together.

A web page with no dynamically updating content is referred to as static — it just shows the same content all the time.

0 Response to "What is JavaScript?"

Post a Comment